The Lost Inspiration of Hagiography

What Catholic mom hasn’t retold the stories of saints to their children? Often it’s the stories of saints that excite the hearts of our children as they find the ones they identify with most, look like them, and share their interests. As parents, we are unaware that we are resurfacing an inspirational literary art form whose intent was lost among our adult literature and has been for some time.

Hagiography is a unique literary genre that writes the stories of holy men and women. The Greek hagios means holy, set apart by God. In early Christianity, Hagiography dates back to the early 2nd century with stories of martyrs and peaks in the Middle Ages. Leading up to the invention of the Gutenberg press and the availability of Scripture to the laity, oral and written stories in the form of Hagiography were often all people had in their conversion to Christianity.

It is crucial for us today to note that Christian Hagiography’s origin wasn’t traditional historical biographies as we know them today. Their primary purpose for centuries and how they were written was to lead the reader to the knowledge of Christ and, ultimately, salvation through the subject’s life. This was done in a style that now seems archaic and “out of touch” with how we write history today. Many details of the saint’s life, even historical accuracies, were either left out or downplayed for the purpose of the work to be achieved. Saints’ actions mimicked Scripture passages, and large passages of other saint stories were repeated in others.

Hagiography did something else critical to early Christianity, starkly evident in the stories of the 2nd-4th century martyrs of the faith. Each writing stressed the idea of the body of Christ as a family. Reading about a Christian believer’s extraordinary life or sacrifice inspired the reader to be part of this family of God. We see this in the earliest works – the Passion of the Scilitan Martyrs, the Martyrdom of St. Polycarp, the Passion of Sts. Perpetua and Felicity and the Life of St. Antony of Egypt.

When Hagiography Died

What happened to the genre, and why does that matter to us today? Hagiography, as previously described in the earliest to middle ages of Christianity, fell out of fashion in Catholicism with the rise of the Renaissance and “died” in Protestant Christianity with the Protestant Reformation.

Hagiography was wrongly redefined as historical biographies. Its uniqueness as a literary genre where the sole purpose was the reader’s conversion was lost.

Three things were lost when this genre (as we knew it to be) changed and began to be associated with a negative connotation in literature.

1. The view of the saint’s life as an invitation to family

Since Hagiography’s sole purpose was to inspire one to join the “family of Saints,” we see a sharp decline in interest in the historical lives of great Christians throughout Christian history from the perspective of family members. As stories of saints began to fall into a category of historical biographies, the view of the saint’s life focused more on curiosities than conversion.

2. The view of the saint’s choices and decisions as insensitive, inappropriate, or errant

Today’s historical biographies wrongly identify a “weakness” in Hagiography. Today, we tend to harshly evaluate past Christians by not ignoring the influence of their time and culture. Hagiography’s perceived weakness of leaving out historical details and accuracies was a key factor of its genre. Doing so helped the reader see the saint’s heart rather than their explicit actions, often unconcerned with context.

Before we judge harshly on their choices, we must see that many of our choices are just as influenced by government structure, political influence, scientific understanding, and educational limitations.

3. The view of the saint’s life as a response to God’s word

Hagiography was instrumental in conversions to the faith. When 15th century St. Ignatius of Loyola lay recovering from a war wound, his entire life was changed by the only two books made available to him, one on the life of Christ and one on the lives of the saints. St. Ignatius is an excellent example of how we should read and digest saint stories. As Catholics, we must realize it’s not either/or. It’s not Scripture or saint stories; the saint’s story arose from a response to Scripture. The two together act as the most powerful witness to the faith.

A New Hagiography

As a convert to the Catholic faith, discovering the lives of the Saints was like opening a treasure chest. As a non-Cahotlilc Christian, they felt hidden behind a curtain and discouraged in favor of contemporary stories of missionaries and preachers.

What can we do today to recapture the spirit of Hagiography as we share the stories of Saints with our children and others?

1. Communicate the saint’s life as a response to Scripture

Where are Christian ancestors left out of historical accuracies and details to focus the story on the heart and conversion of the soul? How can we refocus the account of a Saint’s life as a call to conversion? By tying their story alongside the Word of God.

This makes the saint’s life applicable to our spiritual life rather than our world. Seeing St. Francis of Assisi’s life as a response to “Blessed are the poor in spirit” puts less emphasis on the worldly aspect of his poverty – which can disconnect us from his story – but that of his spiritual reliance on God. St. Francis was deeply inspired by Scripture and wanted to live this word from Christ out in the most obedient way possible. St. Francis’s life isn’t about talking to birds, the extreme poverty of the stylish tonsure that often gets a puzzled reaction from my kids, but about obedience to God’s Word.

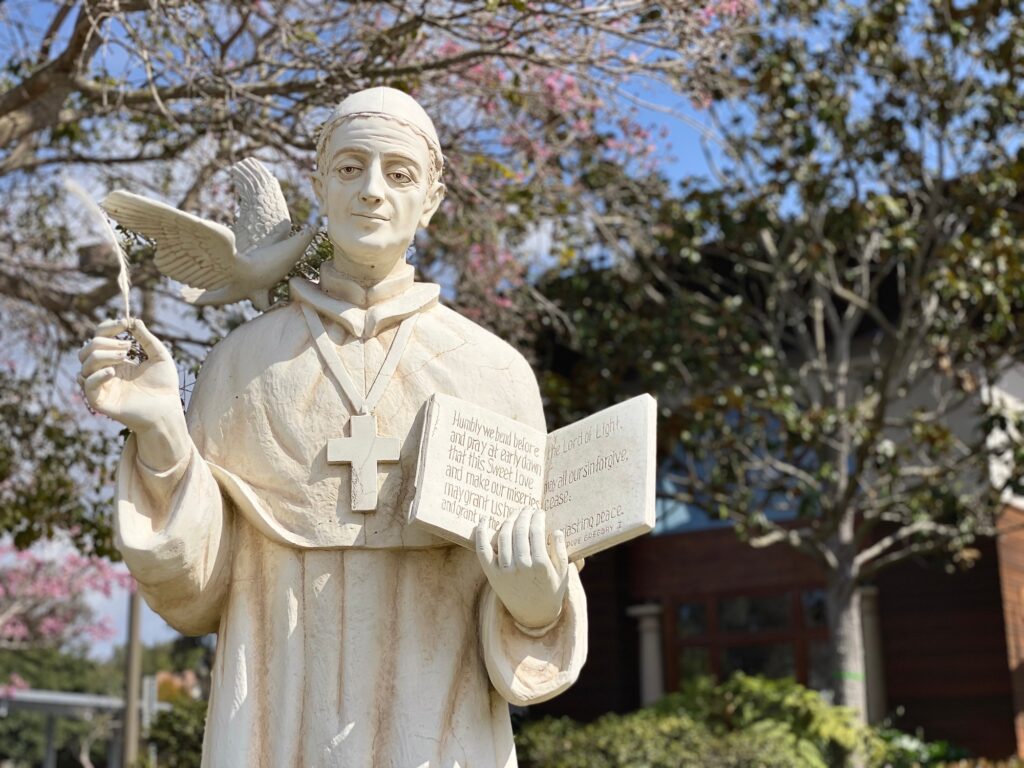

2. Immerse yourself in the eyes of the saints

Everyone loves a good statue, and the statues of the saints were the only “pictures” our Christian ancestors had to tie them to their heavenly family. Statues were meant to be our “family photos.” However, for most modern eyes, they don’t translate. Today, everybody’s photos are Instagram pics. On your social account, you are showing people what you see as a way of showing them yourself. We can do these with saints.

With technology, we can immerse ourselves in the Instagram account of the saint, where they lived, what they ate, read, and listened to. By leveraging technology, research online, images, and videos, we can share in the family memories to unite with how their time provided a well-tilled soil for the love of God to grow.

3. Find the challenge in their story and prayerfully apply it to your own life

Hagiography’s climax was always in the saint’s death and the joining of that saint to the heavenly realm. It was written in a way for the reader to remember their own death and seek out their challenges bravely, knowing that they, too, would die and stand before God. Not the uplifting endings our stories aim for today.

Hagiography makes the reader feel convicted and challenged. The feeling of discomfort is not encouraged in today’s society, but it is much needed if we are to learn from our family members. What do we do with it? The discomfort should be brought to God in prayer to further unite us to Christ.

All In The Family

Reviewing the lives of holy men and women through the eyes of Scripture, their experiences and their death as a means of spiritual nourishment draws us into the family of God. Much like the story shared over the table during a Thanksgiving meal, they are meant to draw us into relationships in the family.

If reading Scripture could be portrayed as food for our soul, then reading the lives of Saints should be likened to a cool drink of water that refreshes and enhances the digestion of that meal.

It’s time we resurrect a new kind of Hagiography, the stories of holy lives enriched by Scripture, enhanced by new technologies to see the world as they did, all while being challenged to stay focused on our salvation as we yearn to reunite our heavenly family in Christ.